My name is Stephen Collins Foster, and I was born in the rolling hills of Pennsylvania in a little town called Lawrenceville on July the 4th, 1826. Music was my calling from the start—though I had no grand schooling in it, just a love for melody and a knack for putting words to tunes that could touch the heart.

Some called me the father of American music, but I was just a man trying to capture the spirit of the people, whether in the parlour or the fields, on riverboats or in grand halls. My songs, Oh Susanna, Camp Town Races, My Old Kentucky Home, Beautiful dreamer—they spread far and wide, carried on the lips of strangers, though fame never filled my pockets. I wrote for minstrel shows, for families gathered around pianos, for those longing for home. And yet, while my music lived in joy, my life was not always so. Misfortune followed me like a shadow, my pockets often empty, my heart heavy.

New York was where I spent my last days, alone in a boarding house, my health failing, my songs known but my name fading. When I passed in 1864, at only 37, I had but 38 cents to my name and a scrap of paper with the words — ‘dear friends and gentle hearts’. But perhaps that is what I was, a friend to gentle hearts, a weaver of melodies that still hum through time. If my tunes bring comfort, if they carry a memory, then maybe I was never poor after all.

My melodies come from the hum of the riverboats, the laughter and sorrow of the people, the hymns of the church, and the distant echoes of old ballads. They come from the rolling hills of Pennsylvania, the voices of those who long for home, the rhythm of work songs, and the lullabies of mothers.

I have never seen the South with my own eyes, but I have heard its music in the stories people tell, in the spirit of those who live and labor there. My songs rise from the old Scottish and Irish airs my family sang, from the simple chords played in parlours, and from the great longing we all share — For love, for comfort, for something familiar in a world that moves too fast. More than anything, my melodies come from the heart. A tune once caught lingers in the mind, but it must be felt in the soul to truly live. If my songs have found a home in others, then they have found the place they were meant to be.

I grew up surrounded by music, though not the kind one learns from books alone. In our home, my older sisters played the piano, filling the house with hymns and parlour songs. My brother brought home the sounds of the world, Scottish and Irish ballads, lively jigs, and the melodies of the theatre. Beyond our door, music drifted in from the streets, from riverboats rolling down the Ohio, from fiddlers and banjo pickers at country dances. I heard minstrel tunes with their rhythms borrowed from African and folk traditions, played in traveling shows.

The churches rang with sacred harmonies, and the fields carried work songs that told stories of hardship and longing. In those days, music was not just for concert halls. It was for the hearth, the campfire, the gathering of friends. It was played by the wealthy on fine pianos and by the poor on homemade fiddles. It belonged to everyone. And as a boy, I listened, listened, and learned until I found my own way of setting those melodies free.

My brother Morrison was twelve years older than me, almost like a second father in some ways. He was the one who brought the wider world into our home, books, music, ideas. He had a sharp mind for business and politics, but he also had a love for culture and education. I suppose you could say he was my first patron, the one who encouraged me when others might have told me to pursue something more practical. When I was still a boy, Morrison went off to fight in the Mexican-American War, and I was left to my own music. But even from afar, he remained an influence.

Later, he helped me publish my first songs, guiding me as best he could. Yet we were different men. He had ambition for business. I had ambition for melody. We had our share of distance, of misunderstandings, as brothers often do. He wanted me to take better care of my affairs, to make something stable of my talent. But I was always chasing the next song, the next feeling. In the end, I think he saw my genius, but he also saw my weakness—how I let fortune slip through my fingers. He did what he could for me, though I fear I was always just out of reach.

My hometown of Lawrenceville, Pennsylvania was just outside the growing city of Pittsburgh. It was a small town, but already bustling with industry, its streets filled with the scent of iron and coal, its rivers alive with the movement of steamboats and barges. The Allegheny River flowed nearby, carrying goods and people westward, connecting us to the wider world. The town itself was a mix of old and new, where fine brick houses stood beside wooden shops, and the clang of the blacksmith's hammer echoed alongside the ringing of church bells. My father, William Foster, was among its early settlers working in business and politics, and our home was one of books, music, and conversation.

Beyond the streets the hills rolled green in the spring and the winters came cold and sharp. It was a place of industry, ambition and change. A place where a young boy could listen to the sounds of the world passing by and dream of setting them to music.

My father, William Foster, came from Virginia, born in the Tidewater country where history and tradition ran deep. He was a man of business and politics, once prosperous but never quite able to hold on to fortune. He served in the War of 1812 and later tried his hand at many ventures, always chasing success but often finding misfortune instead.

My mother, Elizabeth Cleland Tomlinson Foster, was from Delaware, raised with a strong sense of faith and family. She was the heart of our home—kind, patient, and ever watchful over her children. It was from her that I learned the hymns and melodies of old, the songs sung in parlours and by firelight. My family's roots stretch back across the Atlantic, carried over by those who sought new opportunities in a young and growing land. My father's ancestors came from England, settling in Virginia generations before my time. They were part of that old stock of early American families—men of enterprise and service, shaping the course of the colonies as they became a nation.

My mother's family, the Tomlinsons, also traced their lineage to England, though by the time of my birth they had long been settled in Delaware. Their blood carried the traditions of the Old World, but their lives were firmly planted in the soil of America. Like so many in this country, my family's story was one of migration, of leaving behind the known for the promise of something greater.

From England's shores to the hills of Pennsylvania, each generation carried with it a piece of the past, woven into the fabric of the new. And perhaps, in some way, my music carried those echoes too, old melodies reborn in a land of endless possibility.

In my younger years, I was not known as a drunkard — I was a dreamer, a writer, a man lost in his music. But as time passed, the weight of misfortune pressed harder upon me. Success, when it came, was fleeting. Money slipped through my fingers as publishers took more than they gave. By the time I reached my thirties, drink had become both solace and sickness. It was there when I struggled to write, when the songs would not come as easily as before. It was there when my wife, Jane, and I drifted apart, when my health began to fail, when the world seemed to move on without me.

Perhaps I drank to ease the loneliness, or to forget the promises of fortune that never quite came true. But in the end, it did not soothe me. It only took me further from the life I had once hoped to live. I met Jane McDowell in Pittsburgh. She was a fine young woman, full of life and charm, with a beauty that inspired one of my most beloved songs, Genie with the Light Brown Hair. Though the song came later, it was written with her in mind, for she was the genie of my heart. Jane came from a respectable family, and in many ways she was stronger than I. Where I was lost in melodies and verses, she was grounded, practical. We married in 1850, full of hope for a happy life together but as time went on my struggles with money, with work, with drink—all these things took their toll.

We had a daughter Marion but even the joy of fatherhood could not keep my troubles at bay. Our marriage was not an easy one. There were long separations, misunderstandings, and disappointments. Jane left me for a time, weary of my inability to provide. And though we reconciled in the end, the years had worn us both down. She was a good woman, a patient one, but I fear I gave her more sorrow than song.

When I wrote Oh Susanna in 1847, I wanted something lively, something that would make people tap their feet and smile. No, there was no single Susanna, at least not one of flesh and blood. She was born from melody and imagination, a name that fit the rhythm and spirit of the song. It was never meant to be a ballad of true love nor the portrait of a real woman but rather a song of movement and joy of travel and adventure—much like the country itself at that time—ever pressing westward.

Some say it was inspired by a girl I knew, but if that were true, her name is lost to memory. What remains is the song, sung by countless voices over the years, a tune as free as the wind. And in that way, Susanna became real. Not as a single person, but as a spirit carried in music, a name that belongs to everyone who sings her song.

Ah, the Glendy Burke, now that was a name that belonged to something real. There was indeed a steamboat by that name a fine vessel that once travelled the Mississippi, carrying goods and passengers through the heart of the country. I wrote the Glendy Burke as a lively riverboat song, meant to capture the energy and movement of those great steamers that kept the waters alive with song and commerce. The Mississippi and Ohio rivers were the veins of America in my time, and the boats that sailed them were full of stories of captains, deckhands, travellers, and dreamers. The real Glendy Burke was named for a businessman, Glendy Burke, from New Orleans, a man of trade and enterprise. Whether he ever knew his name had found its way into song, I cannot say. But his steamboat and the spirit of those river days live on in the tune. So yes, the Glendy Burke was real, though the song made her something more—an anthem of movement, of journeying ever onward, much like my music itself.

Massa's in the Cold, Cold Ground was a song of mourning, a lament sung from the perspective of enslaved people grieving the death of their master. I wrote it in 1852, and though it was composed in the minstrel tradition, it carried a sorrowful tone, more reflective than some of my earlier, livelier works. I sought to capture the feeling of loss, of change, and of the passage of time. The song speaks of an old master who has passed away, and those who worked his land now remember him with a kind of sentimental reverence.

Whether that sentiment was realistic or merely part of the minstrel style of the time is a question that lingers. I never saw the South with my own eyes, but through music, I tried to paint a picture of its songs, its people, and its emotions as I imagined them.

Massa's In the Cold, Cold Ground was not meant as a song of politics, but as one of sadness, of how death, no matter who it claims, leaves behind a quiet emptiness.

Swanee River, originally titled Old Folks at Home, is in fact a real river, though I had never seen it when I wrote the song. It flows through Georgia and Florida, winding its way to the Gulf of Mexico. When I was composing Old Folks at Home in 1851, I wanted a river name that carried a certain musical quality, something that evoked nostalgia and longing for home. I first considered the Pee Dee River, but found it lacking the right melody. My brother Morrison, always eager to offer advice, found the name Suwanee on a map of Florida and suggested it instead. I shortened it to Swanee to better fit the rhythm of the song. Though I had no personal connection to the river, the song gave it a life beyond its waters, turning it into a symbol of home and memory for many who heard it. And so, in a way, Swanee River became more than just a place on a map. It became a place of the heart, where dreams of the past still flow like a gentle current.

My songs found their way into many places, carried on the voices of those who sang them. They were played in the parlours of fine homes, where families gathered around the piano to sing Beautiful Dreamer or Genie with the Light Brown Hair. They echoed in concert halls, where trained musicians gave them grand arrangements. But my music was not just for the elite—It was sung in taverns and on street corners, on riverboats drifting down the Mississippi and in the camps of weary travellers heading west. Soldiers hummed them in the quiet of the night, and workers sang them to pass the long hours of labor. And, of course, many of my songs were performed in minstrel shows, where traveling troops entertained audiences with lively tunes and exaggerated portrayals of Southern life. It was through these minstrel performances that many of my songs first reached the public, spreading far beyond Pittsburgh, far beyond the North, even into the very South I had never seen.

My music lived wherever people gathered, wherever voices joined in song—whether in joy, sorrow, longing, or laughter. It was not confined to one place, but carried in the hearts of those who found something of themselves within the melody.

Oh Susanna was the song that first made my name known, but old folks at home was the one that brought me the most income. When I wrote it in 1851, I sold the rights to E.P. Christie, the minstrel performer, for a flat fee of $15. He published it under his name at first, a common practice in those days—though my name was later restored.

The song quickly became a great success, spreading across the country, and it remained one of my most popular works. Even so, the music publishing business was not kind to composers, royalties were scarce, and though Old Folks at Home sold thousands upon thousands of copies, I saw only a fraction of its earnings. Had I been wiser in business, perhaps I would have lived in greater comfort, but I was a songwriter first, not a businessman. Still, if success is measured not in coins but in how far a song travels, then Old Folks at Home carried my voice farther than I ever could have imagined.

My last song was Beautiful Dreamer, though I did not live to see how far it would travel. It was published in 1864, the year of my death, and I like to think of it as a farewell, though I did not know it at the time. Beautiful Dreamer was different from the minstrel tunes and lively songs that had once made my name. It was quiet, wistful—a song not of revelry, but of rest. It spoke of a dreamer, undisturbed by the troubles of the world, waiting for the morning light to bring peace. I wonder now if I was writing to myself—to the man I had become, weary and longing for something beyond the struggle.

It was not the kind of song that made great fortunes, nor did it stir armies or fill concert halls, but it was gentle and true, and perhaps that is why it endured. If my life had been full of hardship, my final song was a whisper of something softer, a melody not for grand applause, but for those quiet moments when the world fades and only the music remains.

The Civil War was a storm that shattered the nation, and like so many others, I did not escape its reach. My songs had once travelled freely across the land, sung in parlours and on riverboats, from north to south. But as the country split in two, so too did the spirit of music. It no longer united, but became a tool of division, of rallying cries and laments for a broken land. Many of my songs had been embraced in the South, especially My Old Kentucky Home, which some mistook as a song of fond nostalgia, rather than a quiet lament against slavery. And yet, I had never set foot in the South. I was a son of Pennsylvania of the North, and when the war came, my loyalties remained there. But while the war brought patriotism and fervour to many, it brought hardship to me.

My style of music, so popular before, was fading. The nation no longer had the same taste for sentimental ballads or minstrel tunes. It was now a time of martial music, of anthems for battle. I tried to write war songs, even publishing We Are Coming, Father Abraham — but I could not capture the fire of war the way I had captured the melancholy of home and longing. The war also deepened my struggles. I had long battled poverty, but as times grew harder, so did my circumstances. My songs no longer brought the income they once did. Publishers took advantage, money was scarce, and my health was failing. My wife, Jane, and I spent more time apart, and the loneliness weighed on me. By the time the war neared its end, I was living in a boarding house in New York, nearly destitute.

In 1864, I suffered a fall, a terrible injury that left me weak and fading. I died with little to my name but a scrap of paper that read — ‘Dear Friends and Gentle Hearts’. So, in truth, the war did not lift me up, it swallowed me as it did so many. But my songs lived on, carried by soldiers, by families, by those who still found something in them worth singing. And perhaps that is all a songwriter can ask for, to be remembered not for the hardships, but for the echoes of a melody that still lingers after he is gone.

—

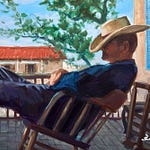

Original post from Bob Dylan through Instagram —

YouTube version:

A recording of me reading this —

My recording of Stephen Foster speaking from the grave — via Bob Dylan

— My name is Stephen Collins Foster, and I was born in the rolling hills of Pennsylvania in a little town called Lawrenceville on July the 4th, 1826. Music was my calling from the start—though I had no grand schooling in it, just a love for melody and a knack for putting words to tunes that could touch the heart.

My reading, Instagram version —

Best wishes,

nightly moth.

http://www.nightlymothpaintings.space

Share this post